Sports Injuries

Muscle tears

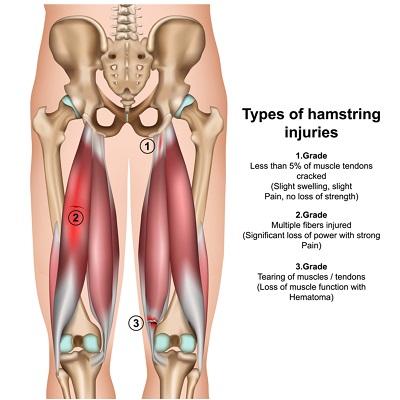

The muscles of the lower limb, particularly the hamstrings and calf, are the most common site of muscle tears and strains.

A tear occurs when the load placed upon a muscle exceeds its capacity. This can happen when a person is forcefully contracting the muscle as with running/sprinting or when overstretching the muscle when slipping or doing the ‘splits’.

Muscle tears can be graded 1-3 depending on their severity. A grade 1 tear may only present with tightness being the major symptom. It is important to recognise this as further activity may see the tear increase in severity. Tears of lesser severity may also only be felt once the body has cooled down after the activity or even the following day.

Grade 2 and 3 injuries are more painful and there is always associated weakness on muscle testing. With these more serious injuries the patient will often feel a sudden, painful event akin to being ‘shot in the leg’.

It is usually possible to diagnose the grade of tear with a physical examination without the need for a scan. However, in instance where there is suspicion of more serious injury such as an avulsion fracture or Achilles tendon tear an MRI or ultrasound may be useful.

Prognosis and complications?

Most muscle tears will heal with proper treatment and adequate rest. It usually takes anywhere from 10 days to 12 weeks depending on the injury severity to make a full recovery.

The main complication seen is re-tearing. Early return to sport/activity and inadequate rehabilitation are the two main factors that lead to muscle re-tears. A muscle tear heals by filling in the injured site with scar tissue in a similar fashion to how your skin repairs itself when broken. Initially this scar tissue is weak and lacks flexibility, however over time it develops more strength and elasticity. If a person returns to activity before the scar tissue is allowed to mature it is more likely to tear again. With each re-tear the length of rehabilitation needed to return to full strength is increased.

Pain is not the only symptom to consider when contemplating a return to sport or activity. Pain can settle relatively quickly after a muscle tear and too frequently we see athletes return to play once they are pain free. At this stage, however, the scar tissue is often still immature and the risk of re-injury is quite high. We like to see a patient return to sport once full flexibility and strength is restored and they have passed a few tests which challenge the muscle integrity. This might include jogging, jumping or hopping.

Physiotherapy is recommended in the acute stages to decrease pain and swelling. Electrotherapy modalities like interferential therapy can have some benefit in the early stages. For more serious injuries crutches or other assistive devices may be needed to rest the area. As the injury settles both massage and therapeutic exercises help to promote scar tissue that is strong and elastic. Without a proper rehab a poorer quality of scar tissue prone to reinjury may develop.

Tendinopathy

Tendinopathy, also referred to as tendonitis or tendinosis, is an overuse injury characterised by pain, impaired function and sometimes swelling in the tendons. Tendon is a flexible cord of fibrous collagen tissue that connects muscles to bones. Whilst these structures can tear, the most common form of injury is from overuse.

Tendinopathy usually occurs due to the tendon being repeatedly loaded beyond the forces it has been conditioned to withstand. As such, we usually see this injury in people who are starting up a new activity they aren't used to, or participating in activities that involve repetitive movements, e.g. long-distance running.

If injured, tendon typically heals quite slowly because is has less bloody supply than other soft tissues in the body, like muscles. Typically, tendon issues are at their worst first thing in the morning, or when getting up after a period of immobility. They usually warm up with activity, as increases in heat lead to more elasticity in the collagen fibres.

The terms tendinopathy, tendonitis, and tendinosis are commonly used interchangeably. This is actually an incorrect use of terminology – they are caused by different pathological processes, require different treatment and are different conditions.

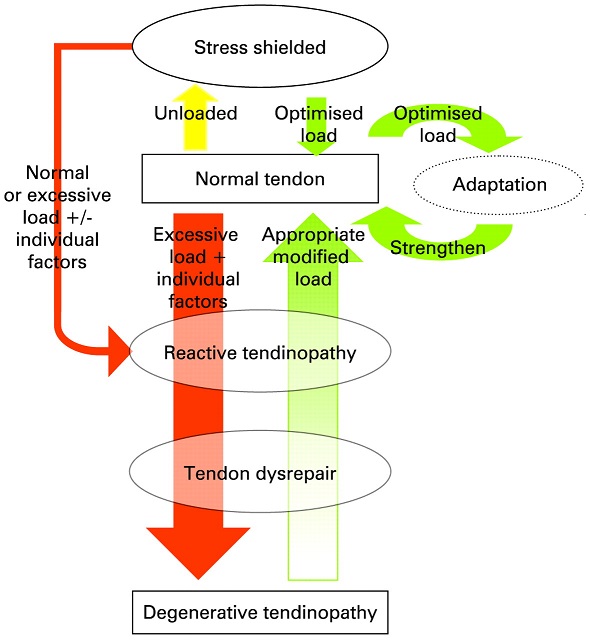

Tendinopathy is a collective word, simply meaning 'pathology in the tendon' and does not relate to a specific condition. There are two types of tendinopathy: tendonitis and tendinosis. These usually exist along a continuum, and over time your tendon pathology can change. It is important to determine where you lie along this continuum, distinguishing between the two conditions before proceeding with treatment. Many health professionals do not make this distinction and as a result misdiagnose tendon problems, leading to a poor outcome for the patient.

Tendonitis is an inflammatory condition – when the suffix 'itis' is used at the end of a word, it always refers to inflammation. These injuries are far less common than people think, and many health professionals still use this term out of habit when describing tendinopathy. Tendinosis (degenerative change in the tendon) will often develop from this, therefore managing this issue properly is very important.

Tendinosis is a noninflammatory degenerative condition that is characterised by collagen degeneration in the tendon due to repetitive overloading. This is much more common and occurs throughout our lifetime. Due to their degenerative rather than inflammatory nature, they do not respond well to corticosteroid injections or other anti-inflammatory treatments (in fact this can weaken them further). They are best treated with functional rehabilitation, activity modification, and manual therapy guided by a physiotherapist.

Physiotherapy guidance is especially important for people with recurrent episodes of tendinopathy. Tendons can become stuck in a degenerative cycle, characterised by periods of short-lived improvement before pain returns, sometimes worse than before. If tendon load is not managed correctly this cycle will continue – physiotherapy intervention is targeted towards strengthening and adaptation of the tendon. This is described in the diagram below:

If you suspect you might have a tendon problem, it is important that you seek medical help from someone who can identify the type of tendinopathy you are experiencing. Your physiotherapist will do this through specific questioning about your symptoms and physical assessment of the area.